Modernism through Five European designers

In the second half of the 19th century, global industrialization accelerated, capitalism developed, and science and technology became increasingly advanced. In this context, new ideas in psychology, philosophy and political theory emerged, and the Victorian morality and aesthetics could no longer meet the needs of the times. Together with the influence of the Neues Bauen Movement and the Art Moderne Movement, architects abandoned tradition, focused on the basic functions of architecture, removed decorative burdens, and utilized new building technologies such as steel and concrete, thus leading to Modernism. After World War I, the modernist trend also became known as the International Style.

Because of the evolution of architectural principles, home deco designers also began to shift from decorative to minimalist design, rejecting Art Deco, Victorian style and neoclassicism. Previously gilded carved wood and rich fabric patterns gave way to metal and simple geometric shapes, and furniture forms changed visually from heavy to light. Today we'll look at how modernism was presented through the stories of five European designers.

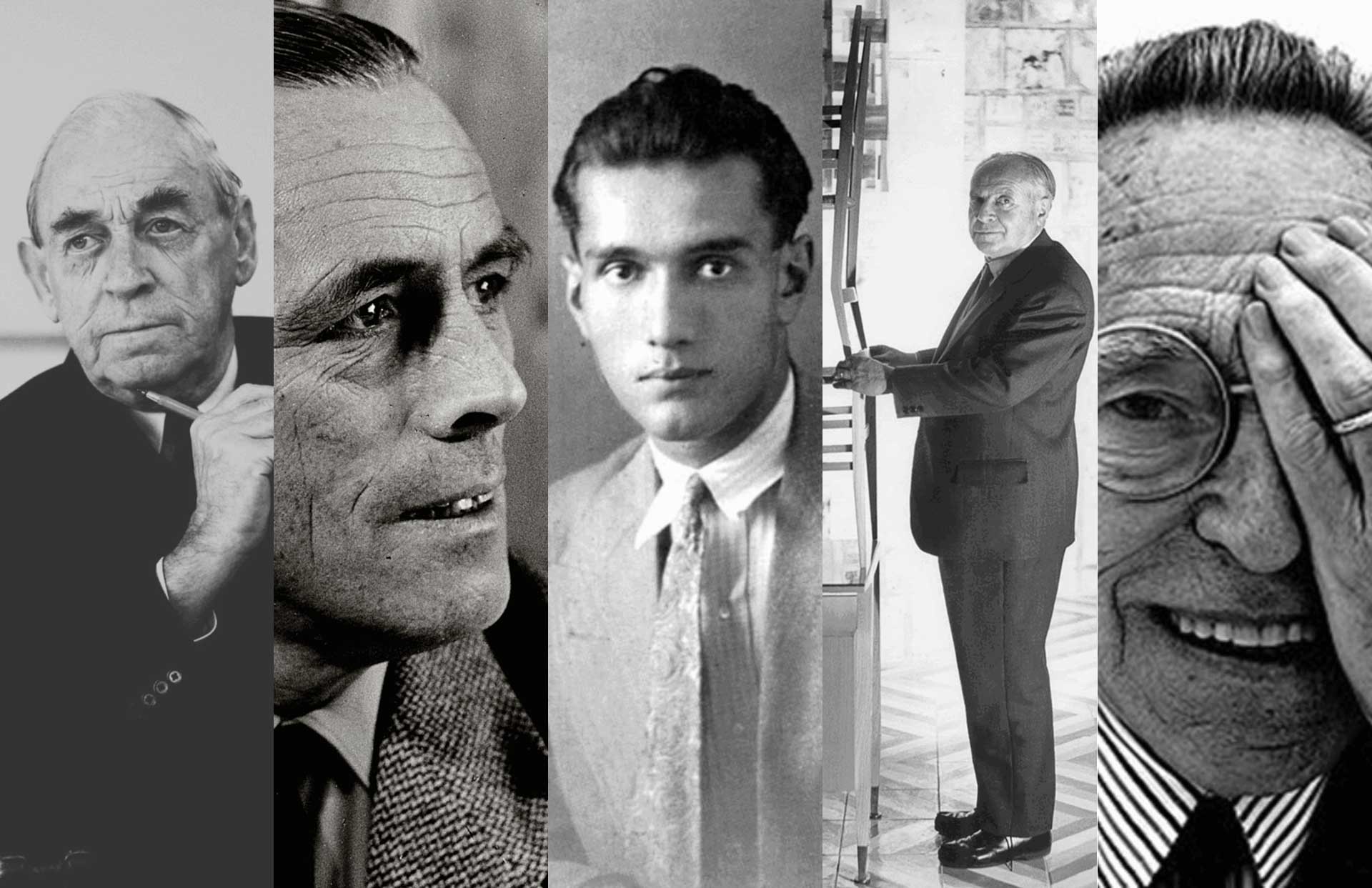

1. Alvar Aalto

Father of Modernism in North Europe

Alvar Aalto was born in Finland in 1888 and graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at Helsinki University of Technology in 1921, and is the father of Nordic Modernism and the advocate of the theory of humanistic architecture. He advocated that everything should be done from the user's point of view and that the designer's ideas should take second place.

Early on, Alvar Aalto's design style was Scandinavian classicism, but in 1924, he came to Italy on his honeymoon with his wife and perceived a Mediterranean design style that has influenced him throughout his life. He said this: "The towns built on the hills of Italy ...... is the purest, most personal and natural form of urban design." Since then his design style began to slowly transition to modernism.

After the 1940s, Alvar Aalto developed an organic modernist style. In Aalto's modernist designs, practicality and romance are combined, and nature and humanistic concerns make the architecture more humane. His architectural style is based on local natural conditions, using local traditional raw materials as much as possible, and the lines and layouts in the spaces give an intimate feeling rather than being a product of the industrial machine age.

Alvar Aalto has worked with home furnishing brands such as MisuraEmme, Nikari, Wb Form, etc. Alvar Aalto's furniture pieces have a light and elegant support structure, clear and simple geometry, and an overall natural and sculptural flow. His use of curves is flexible and rhythmic, not bound to the linear forms of modernism. This is his exploration in the modernist phase, breaking the overly rational and monotonous paradigm of early modernism.

As the famous Japanese architect Tadao Ando said, Alvar Aalto's works can only be perceived if you feel them yourself. He laid the theoretical foundation of modern Scandinavian design style and influenced the direction of design development in the world.

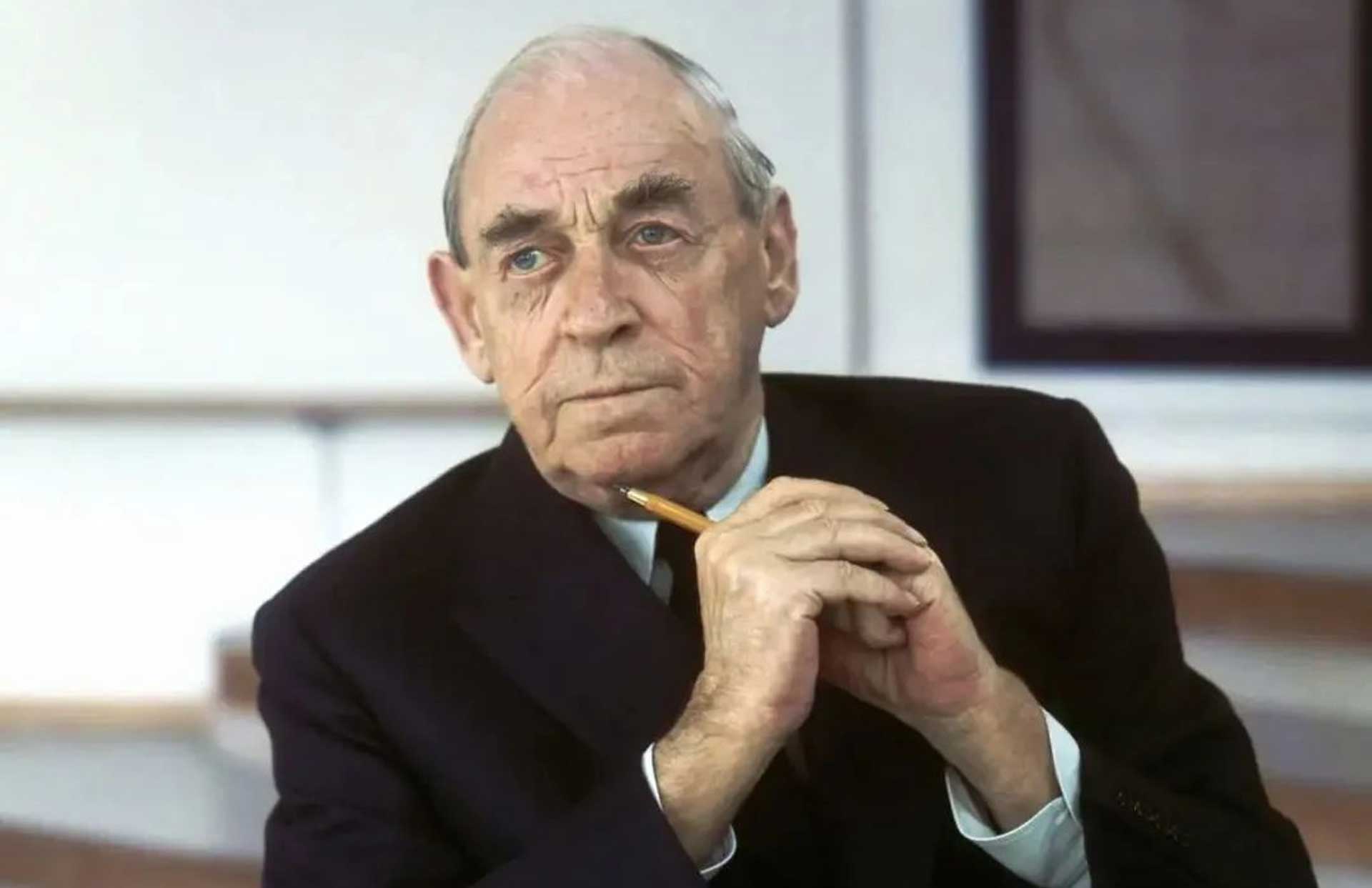

2. Alfred Roth

A Master of Neues Bauen

Alfred Roth was born in Switzerland in 1903 and was a member of the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM), also one of the leading figures of the the Neues Bauen and the Modern Movement. He studied mechanical engineering at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland, and later switched to architecture, graduating in 1926 under the tutelage of Karl Moser, a pioneer of Swiss modern architecture.

Karl Moser helped the young Alfred Roth to find a job in Paris, entering the studio of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret. It was here that he helped the League of Nations in Geneva to design projects in 1927, and later supervised the construction of two residential buildings in Weissenhof, Stuttgart, Germany. Since then he has been a member of the Neues Bauen (New Building) movement.

The Neues Bauen Movement was an important movement in the field of architecture and urban planning in Germany from the 1910s to the 1930s, and the famous Bauhaus Design School was one of the representative institutions of the movement. In the Neues Bauen Movement, architects used new materials: steel, cement, and flat glass, instead of traditional materials: wood, stone, and masonry, opposed elaborate decoration, and emphasized the logical and scientific nature of architectural design rather than the decorative side of visual beauty. They highlighted the economic principle in architectural design, achieving the highest degree of perfection with the lowest investment, making architectural design for the general public, and no longer just for the powerful few. The Neues Bauen movement also greatly influenced the modernist movement.

In 1931, Alfred Roth opened his own studio and worked on important projects in Switzerland, Sweden, the United States and the Middle East. In collaboration with the renowned Hungarian-American architect Marcel Breuer, he designed the Doldertal housing project in Zurich. In addition, he has been a visiting professor at Harvard University, St. Louis University, and the Zurich Polytechnic High School, and has published numerous books on architecture.

Among his few furniture pieces, the most representative one is the AR1 trolley for MisuraEmme. Just by looking at it, its simplicity and functionality have perfectly presented the essence of modernism. We can hardly find any anecdote about Alfred Roth himself, but when we understand Alfred Roth's experience and the background of his time, we can see the light of innovation of the Neues Bauen the Modern Movement from a small piece of furniture.

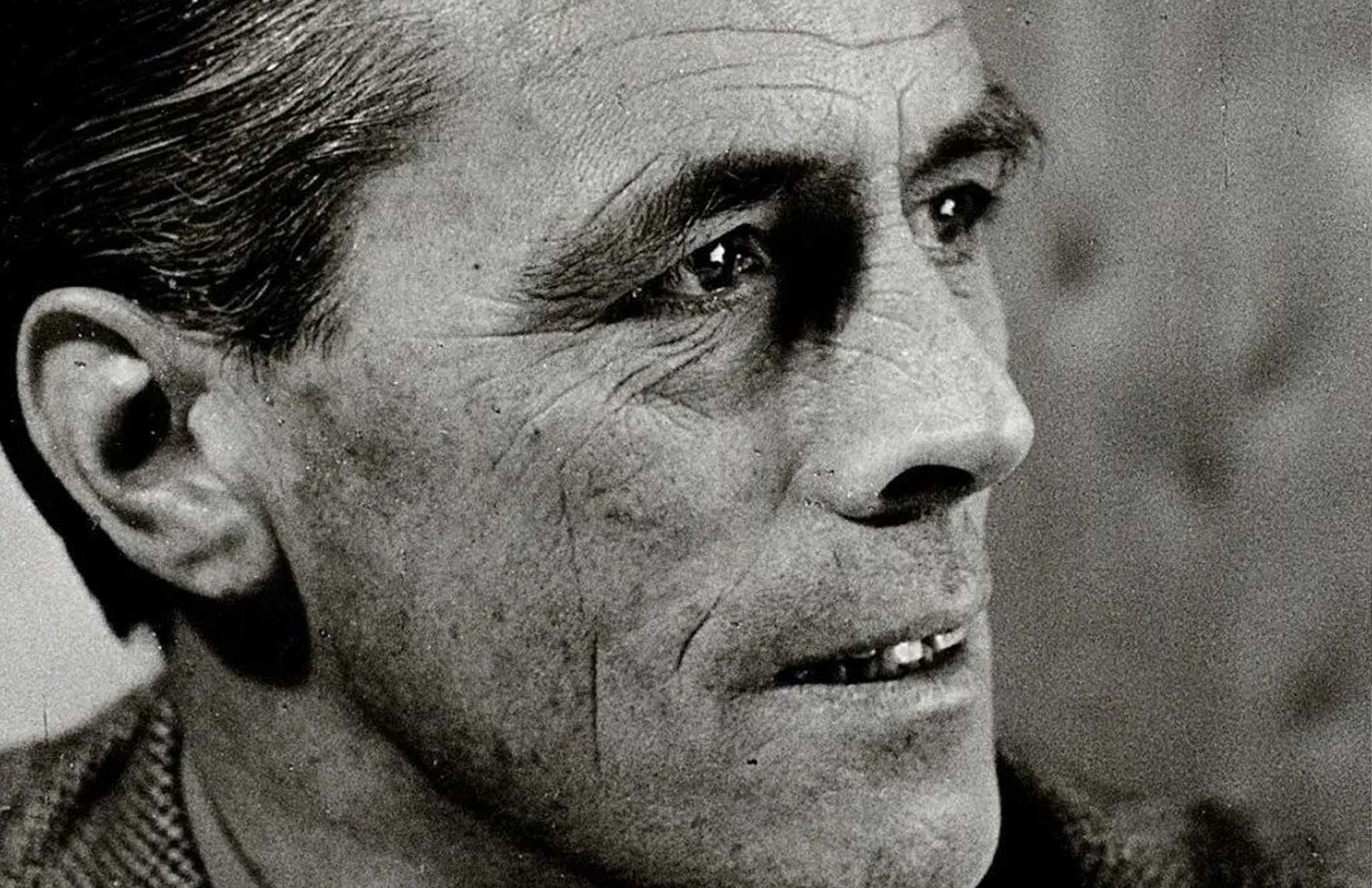

3. Giuseppe Terragni

Leader of Italian Rationalism

Giuseppe Terragni was born in 1904 in Meda, a small town near Milan, and graduated from the Faculty of Architecture of the Politecnico di Milano in 1926. After graduation, he and his classmates Ubaldo Castagnoli, Luigi Figini, Gino Pollini, Guido Frette, and Sebastiano Larco founded the "Group of Seven" of rationalist architects, which led the Rationalist Movement in Italy.

The Italian Rationalist Movement is a modern architectural movement that developed in the 1920s and 1930s together with Modernism, following the principles of functionalism. "The Group of Seven" intended to integrate the spirit of traditional Italian culture and nationalist values into the language of modern architecture, and to combine them with the structural logic of the machine age in a more rational way.

In 1927 Giuseppe Terragni designed the Novocomum Apartments in Como, north of Milan, his first completed work and one of the first in Italy to use modern architectural language. The style was a huge hit in the design world at the time. Another of his well-known projects was the Danteum in Rome. Even though it was not built due to the war, the famous modernist Le Corbusier gave this project very high praise. Le Corbusier stood in front of the Danteum sketches for a long time and said three words: "That is architecture."

With the outbreak of World War II, Giuseppe Terragni went to Eastern Front of the war with the Italian army. Upon his return to Italy, he was treated with electric shocks for mental problems and eventually died of a cerebral thrombosis at the age of only 39. Although his design career was short-lived, his architectural work became a central representative of Italian rationalist and modernist architecture, most notably his Casa del Fascio, which is also considered one of the few valuable legacies of the Fascist for future generations.

In 1936, Terragni began designing the Sant'Elia kindergarten in Como, named after his close friend Antonio Sant'Elia, in tribute to the futuristic architect who tragically died in battle. For this kindergarten project, Terragni designed two versions of the Sant'Elia chair, one for the teacher and one for the children, which later became the Sant'Elia chair we see today produced by Zanotta.

If you are familiar with Zanotta's furniture pieces, you may remember Giuseppe Terragni's Follia chair, which means "madness" in Italian, like the times Giuseppe Terragni lived - full of chaos and darkness when the country was struggling to survive in a dismal economy. His major achievements were accomplished during the reign of Mussolini's Fascist party, and he himself was a staunch Fascist. But also because of the dramatic upheaval, new ideas emerged in architecture and design. Whether this was personal misfortune or artistic luck, would only be judged by future generations.

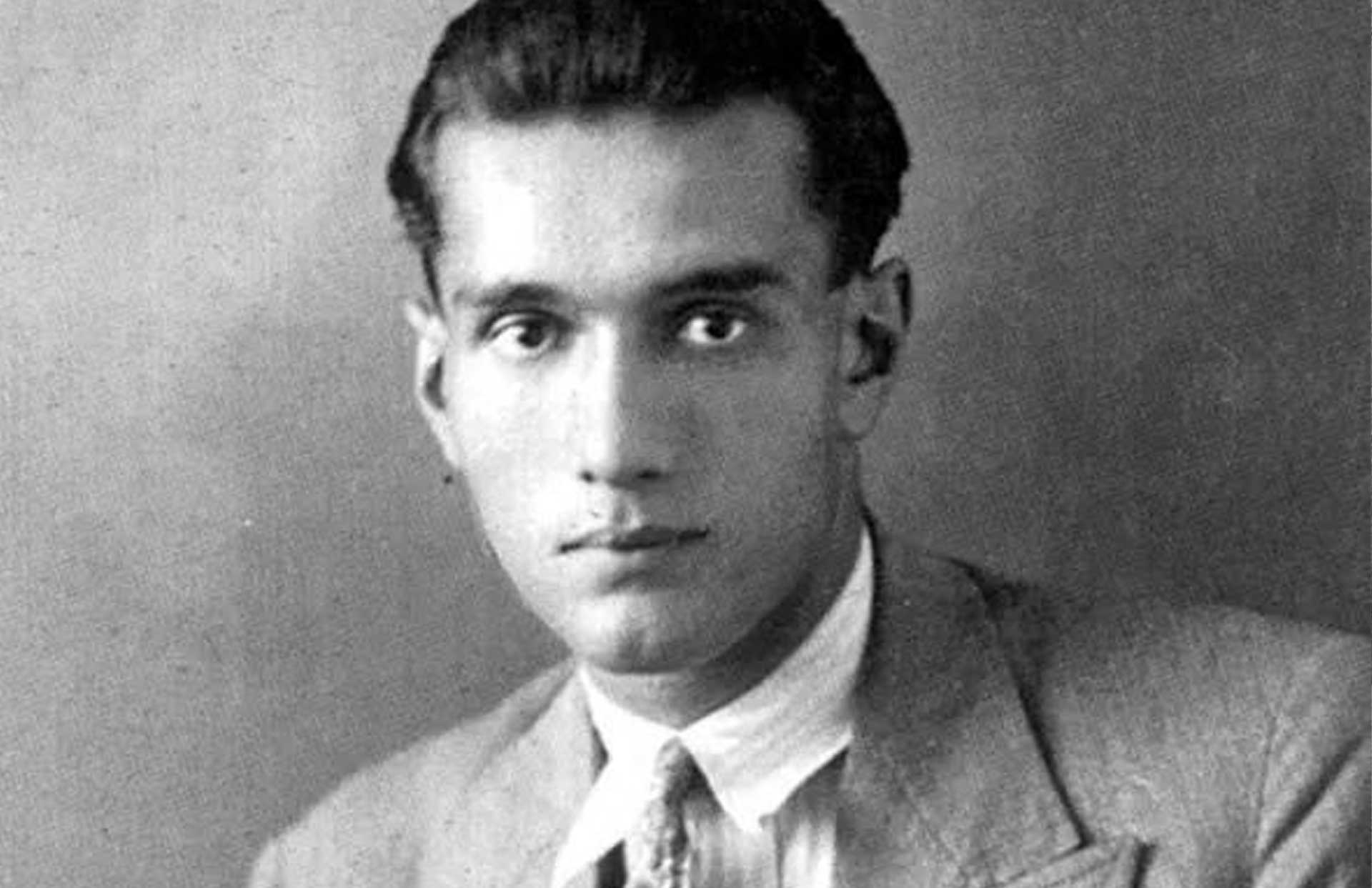

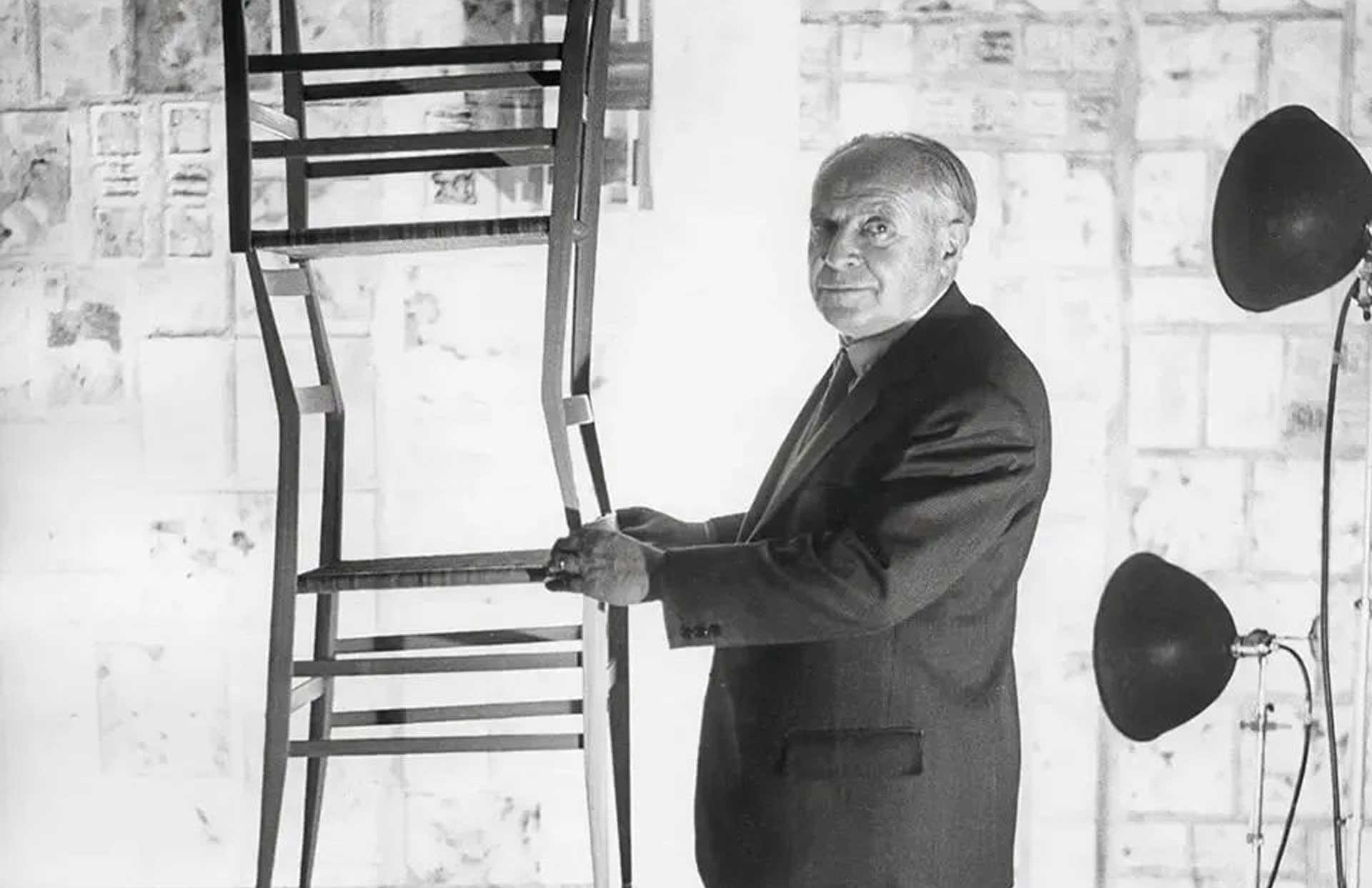

4. Gio Ponti

Father of Italian Modern Design

Gio Ponti, whose full name is Giovanni Ponti, born in Milan, Italy in 1891 and graduated from Politecnico di Milano in 1921, is a giant in design, the all-seeing and all-knowing eye at the tip of the pyramid, the father of modern Italian design.

There is almost nothing Ponti cannot do, as an architect he is also known for designing ceramics, glassware and furniture, and is also active in painting, graphic art, film and theater design - including costumes and sets for La Scala opera house in Milan and its interior design. He had a very prolific life, having worked with over 120 different companies. While he was still alive, he had a close relationship with the Italian rattan furniture family Bonacina1889, for whom he designed many iconic products. After he passed away, many of his designs still came alive through the collaboration between brands and his foundation, such as the famous handmade carpet brand Amini, who selected from Gio Ponti's designs the representative ones suitable for carpet weaving, thus giving birth to the Gio Ponti master collection.

Gio Ponti was also a great professor, writer and advocate of culture, as well as the founder of the well-known design magazine Domus. He said this in a 1952 article in Domus magazine: "Let's go back to the reality where a chair is a chair and a house is a house, and that realistic, authentic, natural and simple design is what we really need." He abhors fussiness and advocates that design should be practical and beautiful, embodying the essence of modernism.

The Pirelli Building, which he designed in 1961, is a slender and elegant building that perfectly reflects Gio Ponti's original intention - to leave more space for traffic and parks in Milan. On the day the building was completed, Ponti exclaimed: "She is so beautiful that I'd love to marry her." The Superleggera chair he designed for Cassina is the embodiment of Gio Ponti's design philosophy - perfect combo of robustness and lightness, technical craftsmanship and design.

In Gio Ponti we can also see that modernism is not just a cold steel and concrete style. Gio Ponti incorporates the personality, creativity and culture of the Italian people into his furniture, objects and architecture, using an extremely wide range of media, and his work is full of sensuality and expressiveness.

Among Italian designers, he was perhaps one of the most charming and generous, and he welcomed everyone to visit his famous open studio, sharing his curiosity about everything to the world. Perhaps the fact that he holds such a high status in the eyes of future generations comes not only from his attainments in design, but also from his easy-going and approachable characteristics.

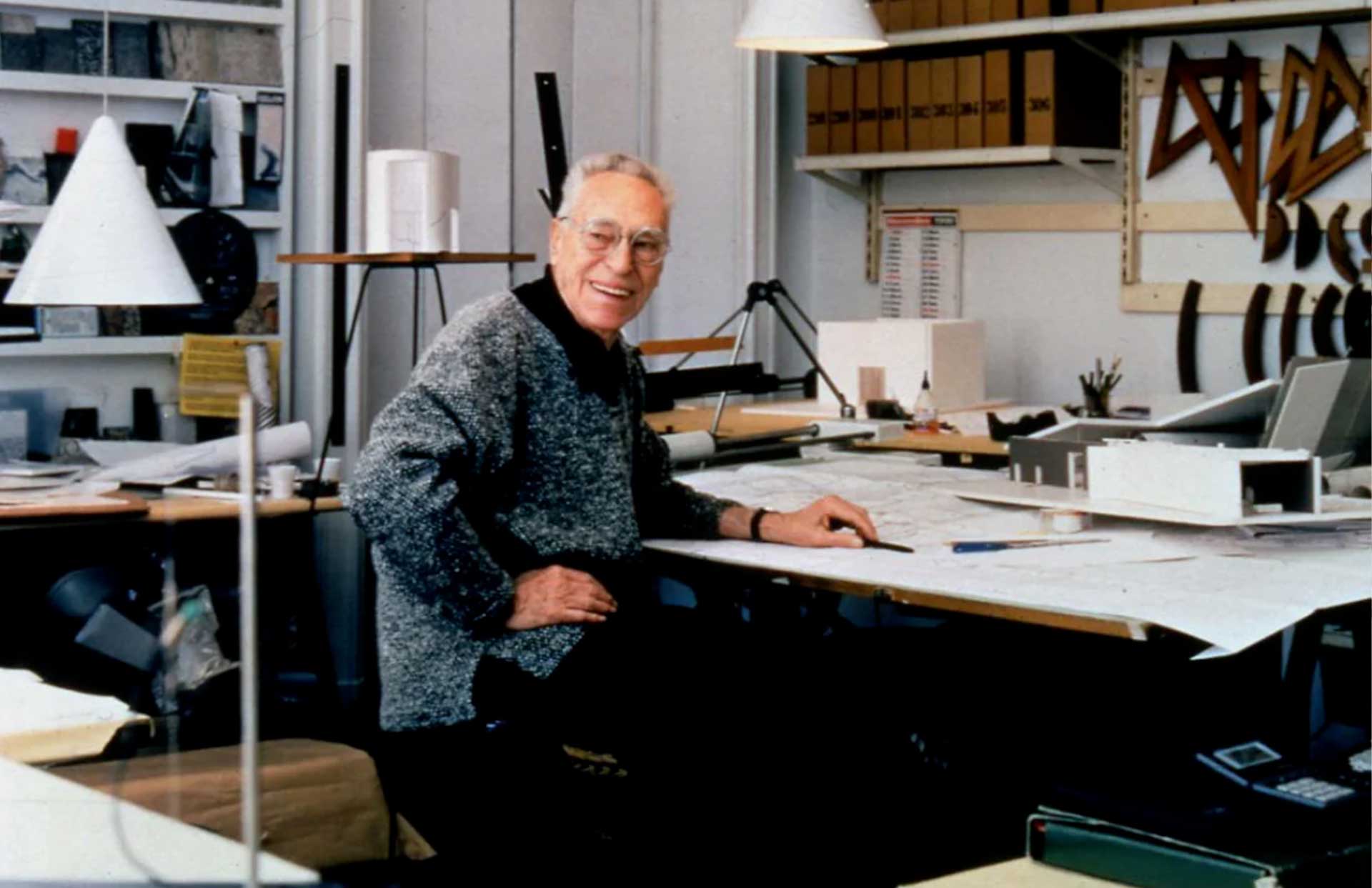

5. Achille Castiglioni

A Design Genius of Creativity and Humor

Achille Castiglioni was born in Milan in 1918, as a famous industrial designer, he was also influenced by the modernist architectural thinking. During his 57-year career, he won the Golden Compass Award - the highest award in the design world - for nine times.

Achille Castiglioni initially worked with his two older brothers, Livio Castiglioni and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, then Livio left the studio and Pier became the most important working partner in Achille's life, and the Castiglioni brothers became known in the industry. Achille collaborated with home deco brands such as De Padova, Flos, Karakter, PoltronaFrau and Zanotta.

Achille Castiglioni likes to look at everyday objects and explore the possibilities of recombining them. For example, Castiglioni was inspired by the look and function of a mundane object like a street lamp, and he created one of the most popular lamps ever for Flos: the Arco, a light source inside a chrome sphere suspended seven feet from a white marble base with a hole for practicality and easy handling. His Toio floor lamp also came from his whimsical idea of "how to turn a car searchlight on the road into a usable object for our home?"

This thinking also extends to his furniture pieces, such as his Mezzadro chair for Zanotta, which simply consists of a "tractor seat", steel frame, bolts and a wooden base, while the Sella chair is a combination of a bicycle seat and a round base, solving the problem of people having to stand up for too long when making phone calls in the 1950s (when most phones were mounted on walls). His use of existing industrial objects was particularly suited to the post-war Italian environment, where materials were scarce, and lent a humorous and contradictory dimension to his designs.

Castiglioni has also witnessed amazing developments in industry and technology, and his Allunaggio chair for Zanotta, a tribute to and celebration of the first moon landing in 1969, was first placed on a lawn, its light form giving the grass maximum room to grow and casting few shadows, making it an elegant and intriguing chair to place indoors as well.

Castiglioni's works always have an elegant sense of humor and fun, such as Brionvega's "smiley radio" RR126. The surface components form a smiley face and it was like by many people as a pet-like music companion. The famous British glam rock godfather David Bowe also owned one.

Paola Antonelli, senior curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a student of Castiglioni's at the Politecnico di Milano, described Castiglioni as "like a comedian from the silent-movie era, nervous, chain-smoking, always in motion, playful, and quite mischievous." In Achille's modernist works, the overall design is uncluttered, and his curiosity and ingenuity subvert the traditional aesthetics and functions of objects, providing witty and simple answers to various life scenarios and revolutionizing the design language.

When we look at modernist architecture and furniture works today, if we don't know much about design history, it's easy to have the stereotype of cold industrial style, but through the above five designers, we may see modernism in a different way now, and each piece of furniture is like a microscopic history, revealing the light of the times and humanity.

As Portuguese modern architect Alvaro Siza said about Alvar Aalto, the father of Scandinavian modernism: "The study of Aalto's buildings is not just to praise his unattainable genius, but on the contrary, to appreciate their rare accessibility. From him, we learn not to follow modernism blindly, but to discover the problems of the present, to face them head-on and to find the way forward."

Organizer: JP Concept China

Producer: Yi

Editor: Xinwei

Image copyright: Websites of various designers and brands